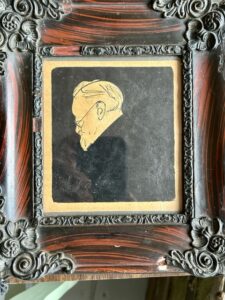

I get in trouble because I make connections which may not exist. On the other hand, I succeed in drawing conclusions because of my experience with connections which SHOULD exist. A case in point: a reader found a drawing of a distinguished man with a beard at a thrift store and wondered about its relevance. How to research? What inference to make? First, I asked him about the era, and what’s happening in this era? Why is the portrayal important? Because, of course, somebody preserved it for 100 years. Who thought it valuable?

I get in trouble because I make connections which may not exist. On the other hand, I succeed in drawing conclusions because of my experience with connections which SHOULD exist. A case in point: a reader found a drawing of a distinguished man with a beard at a thrift store and wondered about its relevance. How to research? What inference to make? First, I asked him about the era, and what’s happening in this era? Why is the portrayal important? Because, of course, somebody preserved it for 100 years. Who thought it valuable?

This serves as a great example of the relationship between objects and people. I remembered a portrait of a Danish writer named Erik Skram (1847-1923), I believed a mono print. When my reader researched it further he found the mono print, either a kind of drawing OR a one-of-a-kind lithograph, “after” a five by five inch photo by a Danish photographer Fred Risse. The reader asked if he should open the paper at the back and look further. “ABSOLUTELY,” I said.

Underneath he found a photograph of the Danish feminist author Amalie Skram.

Underneath he found a photograph of the Danish feminist author Amalie Skram.

Because I’ve written about unsigned works of art, the reader asked some salient questions: “I opened the back. Found a drawing or lithograph of Erik Skram. Underneath I see the photo of Amalie, shot by Fred Risse. I found the prototype photos of Erik, the subject of the litho or drawing, which I see in photos by Fred Risse. What is the relationship between sitters, artists, and the two images?”

The relationship is that Erik’s image and Amalie’s image are framed TOGETHER. And they are after photos by the same photographer who, one can infer, knew them BOTH. That is not a mistake.

Here’s the Skram connection: scandal.

The literary world considered both Erik and Amalie scandalous writers in the last few years of the 19th century in Scandinavia, tangling with feminist issue. Think of the playwright Ibsen.

Amalie wrote four times more important works than her husband Erik Skram. She wrote more socially aware novels than him, more scandalous, and she died unknown. Erik wrote in the same “feminist” vein, died with the title of Knight of Denmark.

In 1996 Amalie’s grave was discovered and marked with a bronze bust of her, a statue placed in Copenhagen, a postage stamp printed in the late 1990s, and a school named after her. Took a while but she got recognized.

I found a double portrait of Amalie and Erik painted by naturalist Harald Scott Moller (1895), in a library in Bergen Norway, her birthplace.

Amalie had an unhappy childhood. Her father abandoned her mother with five kids, which forced Amalie at seventeen into a lucrative marriage with a much older man. Ironically Erik at this time wrote novels about JUST this topic, but from a male perspective. Amalie experienced a major breakdown after seven years of marriage. She spent a few years in a mental hospital. After she gave birth to two boys, she left her husband to move to Copenhagen, where she met Erik, also an author.

Amalie hung in bohemian circles, but no man involved had that pioneering character of Amalie. Amalie gained the courage to write about three major issues. She wrote seventeen plus novels about marriage and female sexuality in 1890s Scandinavia, how women faired over multi generations in Scandinavia, and the abhorrent treatment of females in mental institutions. WOW….

No one cared much until the 1990s when Denmark instituted a prize in her name for influential writers on female issues.

As fate had it, Amalie, once married to Erik, birthed a daughter, went into another nervous breakdown, and wound up committed to a mental institution again. She lost her life six years later.

So now, we see the connection:

The drawing of Erik and photos of Amalie are in the same FRAME, layered together, because that’s the narrative. I often see this in families when someone wants to keep lives together as images. Unknown regarding value. I suggested the reader contact Bruun Rasmussen Auctions in Sweden for more info. I will report back.