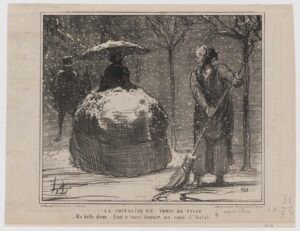

GE sent me a Daumier print of a Parisian woman with a huge bell shaped hoop skirt catching the falling snow. GE asked if women really wore this fashion. What does the figure symbolize? Why this silhouette? What made the skirt grow so big? What happened at the date of this Daumier print (1860s) in the world of Parisian women?

GE sent me a Daumier print of a Parisian woman with a huge bell shaped hoop skirt catching the falling snow. GE asked if women really wore this fashion. What does the figure symbolize? Why this silhouette? What made the skirt grow so big? What happened at the date of this Daumier print (1860s) in the world of Parisian women?

This is the era 1850-1870 of the Second Republic in France, after the Bourbon Royal Louis Phillipe abdicated in 1848. Les Misérables, Victor Hugo‘s novel, takes place during the very beginning of the July Monarchy (1830-1848). In 1848, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte was elected President by a vote taken of men; all men, property owners or not, were allowed to vote. The Second Empire, established by plebiscite on 2 December 1852, made Prince-President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte officially Napoleon III, Emperor of the French.

The Rights of Man

As President and a conservative Catholic, his policies belied his stated campaign belief in the values of the Revolution (1790s). He wanted stability, tradition, and nationalism in his reign. In the light of this, French Republicans wanted government help with employment, bread, and rights.

In the nation that established The Rights of Man (1789), women, especially, had few civil rights. The Napoleonic code (1804), forbad women to enter into legal contracts. Wives couldn’t engage in commerce without a husband’s written permission. All property in a marriage was the husband’s. By 1860 French women were actively protesting to achieve the vote.

In the light of discord, Napoleon III championed growing French industry and capitalism, and championed the remaking of Paris under Baron Hausman, architect of “Modern” Paris (1854-1870). Napoleon actively supported the Algerian War between French colonists against Muslim Algerians.

Women in France questioned the purposes of marriage and their own rights in the light of the conservative regime. Many historians point to the crinoline cage hoop skirt as the outward symbol of a REAL CAGE.

The Ideal Female Body

In 1856 Frenchman RC Milliet invented the cage as a series of steel bands strung together with tapes and wires, a lightweight “volumizing” hoop skirt. Previous fashion emphasized a unique hourglass silhouette. The ideal female body (1840-1860) was a slim torso, dropped shoulders, small waist, and large hips. Crinoline enabled a corseted waist to look even smaller because of the dome shape. Technology enabled the fashionable woman space, air, and movement. She didn’t need to wear numerous heavy petticoats, but one CAGE of five to eight hoops. These cages often stretched six to eight feet wide.

In 1856 Frenchman RC Milliet invented the cage as a series of steel bands strung together with tapes and wires, a lightweight “volumizing” hoop skirt. Previous fashion emphasized a unique hourglass silhouette. The ideal female body (1840-1860) was a slim torso, dropped shoulders, small waist, and large hips. Crinoline enabled a corseted waist to look even smaller because of the dome shape. Technology enabled the fashionable woman space, air, and movement. She didn’t need to wear numerous heavy petticoats, but one CAGE of five to eight hoops. These cages often stretched six to eight feet wide.

Fashionable females ‘took up’ eight feet of floor or street space. They asked for two seats on a bus, they expected men’s help downstairs, or up into carriages. Some historians of fashion say this proved servitude to men and fashion. Today we view the elaborate gown, hoop skirt, and think – those skirts limited the female, but they EMPOWERED the female. Taking up SPACE seemed important in a world where you DO NOT take up political SPACE.

In 1860 male commentators on this fashion wrote that a woman could conceal a pregnancy or hide a man under those hoops. These comments, meant as defensive, show the hoop skirt threatened by its very SIZE. Also, fashion historians point out the sexual nature of the 1860s ‘crinoline debate.’ Men wrote, ‘what are you hiding, my lady? And within your own bell-shaped space, what would I SEE?’

The threat of the female with a large physical presence led to the rise of what we call the New Domesticity. Mid-19th century education trained young girls as wives and mothers. It saw marriage through matchmaking, not passion or romance, the archetype of the good wife vs. the middleclass adulteress. Divorce wasn’t allowed until 1870, which gave birth to a new French word, ‘feminisme.’

Powerful Container for Symbolism

Men’s fashion of the same era became black, plain, and severe, the bland businessman of the 1840-1870s. Middle and upper class men became SOLEMN, and women became elaborate and ‘large.’

Vilification of what a woman wears, and who she is when she dons a costume (Hillary’s pantsuits) is as common today as then. I find it so fascinating that a woman might choose to wear voluminous crinoline as an ART FORM, to create an illusion, to underscore what she is, where she is. How she envisioned WHO she is, was, perhaps, powerful, because the illusion was also a reality.