My 2024 article on how to decipher an illegible artist signature became a big success. Many people send me art to authenticate with questions of fakes and frauds. Gloria wishes she were as lucky as the picker who found a so-called Van Gogh. She sent me a Wall Street Journal article about a small, eighteen by sixteen inch painting at the center of a $15 million dollar battle. Is it a real Van Gogh? The world of scientific art analysis, the LMI Group from NYC, says it is a Van Gogh. Yet many connoisseurs and scholars at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum says it is NOT. The conflict, art and science in fine art authentication has raged since the dawn of the technical revolution in the late 1980s to 1990s.

My 2024 article on how to decipher an illegible artist signature became a big success. Many people send me art to authenticate with questions of fakes and frauds. Gloria wishes she were as lucky as the picker who found a so-called Van Gogh. She sent me a Wall Street Journal article about a small, eighteen by sixteen inch painting at the center of a $15 million dollar battle. Is it a real Van Gogh? The world of scientific art analysis, the LMI Group from NYC, says it is a Van Gogh. Yet many connoisseurs and scholars at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum says it is NOT. The conflict, art and science in fine art authentication has raged since the dawn of the technical revolution in the late 1980s to 1990s.

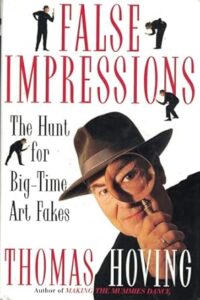

Former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas Hoving, world famous for his books on the primacy of the eye of the connoisseur, opined that an expert’s gut sense is much more reliable than science. In the Van Gogh case we’re talking about some big money for a little work of art. If it’s authentic, the owners might sell for $15M or more. The art world, on the heels of this, noticed many startup scientific art authentication companies, such as the aforementioned LMI Group, founded in 2016.

So, what’s the battle about?

The picker found this painting in 2016 at a Minnesota garage sale for $50. Shortly after they sent photos to the Van Gogh Museum, which said “NOT” Van Gogh. The picker/owner approached the LMI Group, who bought it for an undisclosed amount. Thus, began the costly, to the tune of $30K, research.

The picker found this painting in 2016 at a Minnesota garage sale for $50. Shortly after they sent photos to the Van Gogh Museum, which said “NOT” Van Gogh. The picker/owner approached the LMI Group, who bought it for an undisclosed amount. Thus, began the costly, to the tune of $30K, research.

They proceeded with the authentication of the little image of a strange looking country fisherman shown in three-fourth pose, smoking a short pipe, and mending nets, similar to the work of a lesser known artist in the late 19th century. Is it a copy? And by WHOM? LMI claims Van Gogh painted the fisherman “after” the work of another artist with the same theme. For the many arguments the Van Gogh Museum gave against this attribution, LMI offers counter arguments. For example, the colors are muted and somber, and although the world knows him as a colorist, he also painted (rarely) in browns.

This story reads like a road map of arguments for the future of art authentication in the AI world. The LMI Group, in an almost 500 page scientific exposé, claims their science proves the painting was painted in 1889 towards the end of Van Gogh’s life when he suffered at the Saint Paul Asylum in the South of France. The Van Gogh Museum received the report after they summarily dismissed the original owner’s request for an opinion of authenticity. The LMI Group wrote a press release on January 31,2025 after the Museum reviewed their report. It said the Museum said “NOT” a Van Gogh, again. After all that work!

Who Wins?

Museum directors like Thomas Hoving want to insist the last word goes to the connoisseur, thus the Museum wins. Remembering $15 million plus is at stake, LMI’s report gives a mixture of old fashioned connoisseurship, cutting edge science, and scholarship. Not surprisingly, one of LMI’s directors is the former head of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The LMI Group press release states that new startup art authentication companies—like theirs—aim to “expand and tailor the resources available for art authentication, integrating science and technology with traditional tools of connoisseurship, formal analysis, and provenance research.” If provenance is important, why doesn’t LMI Group explain why the painting was found in a garage in Minnesota?

A picker found a Jackson Pollock in a dumpster in 2006 That work became subjected to scientific analysis—2006 style—of the paint, board, and technique, with inconclusive results. Since then new scientific approaches to art authentication gained popularity and became pricey—and highly technical. But they’re not yet mainstream.

The science tools used?

AI generated visual analysis, chemical pigment tests, fiber tests, test of the glaze used—in this case egg white used as a glaze, a typical practice of Van Gogh. Objects caught in the paint are examined. The LMI Group claimed to find a strand of male red hair. A mathematical analysis of the handwriting style is undertake. In this case the style of the title, ‘ELIMAR’ matches another Van Gogh handwritten title to 94 percent accuracy. The stroke, the length of the letters and the angle and width are analyzed forensically.

AI generated visual analysis, chemical pigment tests, fiber tests, test of the glaze used—in this case egg white used as a glaze, a typical practice of Van Gogh. Objects caught in the paint are examined. The LMI Group claimed to find a strand of male red hair. A mathematical analysis of the handwriting style is undertake. In this case the style of the title, ‘ELIMAR’ matches another Van Gogh handwritten title to 94 percent accuracy. The stroke, the length of the letters and the angle and width are analyzed forensically.

If you’re interested in the expert connoisseur’s side of the expert vs the science argument, I suggest you read the classic book on detecting works NOT authentic by Thomas Hoving: False Impressions: the Hunt for Big Time Art Fakes. Hoving embarrasses some big collectors and major museum collections.

Pingback: News From the Art World - Elizabeth Appraisals