For a year I’ve appraised items in Paradise CA destroyed in the fire of 2018. I’m amazed at the variety of objects treasured and collected by many folks in that community. I experienced the type of objects I don’t appraise much: baseball cards, stamp collections, mineral collections, coin collections, cast iron toys, matchbooks, vintage rock memorabilia, beanie babies, NASCAR stuff, model cars, and taxidermy. Other appraisers before me turned down Paradise jobs because the objects collected were not ‘highbrow’ enough. This classification (judgment) of collections into either highbrow, middlebrow, or lowbrow both intrigued and disgusted me.

For a year I’ve appraised items in Paradise CA destroyed in the fire of 2018. I’m amazed at the variety of objects treasured and collected by many folks in that community. I experienced the type of objects I don’t appraise much: baseball cards, stamp collections, mineral collections, coin collections, cast iron toys, matchbooks, vintage rock memorabilia, beanie babies, NASCAR stuff, model cars, and taxidermy. Other appraisers before me turned down Paradise jobs because the objects collected were not ‘highbrow’ enough. This classification (judgment) of collections into either highbrow, middlebrow, or lowbrow both intrigued and disgusted me.

A collection is a life-affirming structure, and to me it doesn’t matter what is collected. A collection is a passion, a sentiment, a reach into history, and a personal past. Objects in a collection form cultural connections, enable structure building, and celebrate the thrill of the hunt.

Costco’s magazine, Connections, this month featured a story about what Costco customers collect, such as full-service gas station memorabilia, matchbox cars, ceramic owls, ceramic honey pots, a world of patented mousetraps, presidential memorabilia, Pez candy containers, souvenir coffee mugs, ceramic snails, locks, miniature perfume bottles. The writer, T Foster Jones, perhaps didn’t select collections based on refinement, money, connoisseurship, and rarity. Selecting such “highbrow” collections for this publication may have compromised the ‘fast consumer’ mentality Costco symbolizes.

Who originally designated objects as ‘highbrow?’

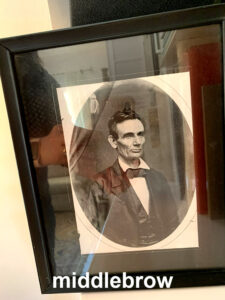

First, in 1880-1900, ‘highbrow’ literally meant a high forehead to a group of ‘scholars of the head’ called phrenologists. These scholars studied the shape of facial features and heads at the turn of the last century. The term applied to the phrenological belief that the higher the brow the more intelligent the person.

First, in 1880-1900, ‘highbrow’ literally meant a high forehead to a group of ‘scholars of the head’ called phrenologists. These scholars studied the shape of facial features and heads at the turn of the last century. The term applied to the phrenological belief that the higher the brow the more intelligent the person.

In 1946 a brilliant editor for Harper’s reinvented the term highbrow to apply to a range (high, middle, and lowbrow) of what collectors CONSUMED during the tenure of Harry Truman. This young editor, Russell Lynes, published a lighthearted, satirical analysis of the state of culture post-WWII, when the median American income was $3,000. The state of culture, he said, was stratified, and always had been, and fell into three main TASTE segments: high, middle, and low. The three categories, he believed, stood for permanent cultural standards.

The electricity generated by Lynes’s article, accompanied by his fantastic socio-diagram cartoon graphs, resulted in a book still worth reading today: The Tastemakers (1954). Lynes famously said in his book that what marks the group ‘highbrow’ wasn’t American heroes, but American thinkers. After WWII, he said, we needed oracles, and the closest we came to oracles were scientists, such as Einstein.

HOW each of us developed a high, middle, or low “brow” taste level depended on whose ideologies we consumed.

A Paradigm Shift

In the 1960s a sociologist posited that the American invention of the Book of the Month Club is a marker that shows ‘certain people’ (middlebrow) DO want high culture, but they want it EASY.

In the 1960s a sociologist posited that the American invention of the Book of the Month Club is a marker that shows ‘certain people’ (middlebrow) DO want high culture, but they want it EASY.

In 1990 another genius, Lawrence Levine, rethought “high, middle and low BROW-NESS” in Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (The William E Massey Sr., Lectures in American Studies). His book upended the paradigm of high, middle and lowbrow, and stated that cultural boundaries are shifting and fragile, NOT natural and eternal. However, we still use the comparison of a certain group’s appreciation of “art and culture” as a marker of rank/status/brow-ness, today.

The New York Times features articles that deconstruct the high, middle, lowbrow ranking system. Creatives and intellectuals today, they say, watch Netflix and fashions on the street. Intellectuals and creatives purchase and operate middlebrow technology. Sociologists who study the arbitrary divisions of class and taste say that so many visual images and noise surround us that we make little distinction between high, middle, or lowbrow art. They cite today’s creative mashups, compilations, and resonant sharing of music and images across MANY artforms as proof. To polarize a group of Americans because of one’s judgment about taste is a crime in this rich creative landscape.

To judge cultural capital is to polarize others. As Diana Vreeland said, “I would rather have bad taste than no taste at all.”