I think about big and small these days. My world has become smaller. I packed up thousands of my reference art books and left my office because of health concerns. That small office was conducive to big changes for me. After a week of exhausting packing, loading up my garage, torturing my partner, and “refining” a home office (my dining table), a client asked me, “What are the largest object you’re appraising? What are the smallest?” So I offer here examples of those things, and a few reflections on the compression of our lives, our virtual monasticism.

I think about big and small these days. My world has become smaller. I packed up thousands of my reference art books and left my office because of health concerns. That small office was conducive to big changes for me. After a week of exhausting packing, loading up my garage, torturing my partner, and “refining” a home office (my dining table), a client asked me, “What are the largest object you’re appraising? What are the smallest?” So I offer here examples of those things, and a few reflections on the compression of our lives, our virtual monasticism.

I now appraise from home, meeting clients, and seeing objects in small photos or on Zoom. My usually great sense of scale has really changed! I’m not sure if I’m looking, for example, at a little ceramic pot or a massive jardinière. Likewise, people have changed. A client who stands over six feet is now reduced to a one-inch square on the Zoom screen. No one has a body: I can’t tell the size and shape of anyone. That Zoom Hollywood Squares grid pattern has no flow!

Many clients dig out things they always loved and found beautiful, and want to reach me, finally, to know more about those objects. I noticed that many of my clients appreciate things for the beauty they bring, and clients are hungry for knowledge about objects in their limited ‘space’ now, just for the sheer pleasure of obtaining knowledge. Emails to me these days start like this: “I always wondered about this painting. Tell me its history.” Instead of “I want to know what this painting is worth.” Objects attain treasured status because of the memories and pleasures they evoke, not because the object serves the interest of value. What is small is big again.

The biggest objects I’m appraising lately:

An entire fireplace surround, a mantel with an arched opening (I could walk inside), Italian, second half of 19th century, in the Rococo Revival style (value: $56K)

An entire fireplace surround, a mantel with an arched opening (I could walk inside), Italian, second half of 19th century, in the Rococo Revival style (value: $56K)- An entire 19th century English street Gaslamp, 25 feet of cast iron, with a street sign attached ($1,500)

- An eight foot molded copper codfish weathervane, 1910, on a tall shaft over a large copper compass, spinning ($12K)

- A late 19th century stained glass commemorative church window, depicting a striding tall Abraham Lincoln, eight feet ($3K)

- Two rare large pieces of Steiff stuffed animal toys:

-

- A 1950’s two foot crouching starfish, used as a stool ($500)

- A 1950’s mohair camel used as a store display, with halter and colorful tassels, almost six feet tall ($2,500)

-

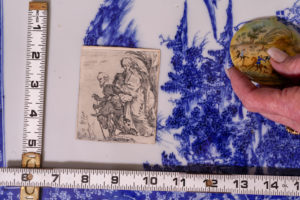

And some of the smallest objects:

A one-inch Japanese Meiji period (1868-1911) carved ivory erotic full-bodied female ($300)

A one-inch Japanese Meiji period (1868-1911) carved ivory erotic full-bodied female ($300)- A one-inch circular formed netsuke of five standing horses, 19th century, with openwork carving ($1,500)

- An English George III solid gold snuff box (1804) with engine-turned (machine) engraving of a crest, hallmarked for London, three by six inch, two ozt ($1,800)

- A five and three-fourths inch 1940’s Mohair stuffed teddy bear, also Steiff, with jointed limbs ($125) given to me my grandmother when I was small

Reflections on Small and Big:

The smallness of our personal world today stands in contrast to the largeness of the tragedies in the big world. Our generation, and younger generations too, experience the frustration of uncertainty. None of us knows what the future may hold.

Although C.S. Lewis lived through a World War while at Oxford, and not a pandemic, these words from his 1939 essay “Learning in Wartime” resonate with me.

“We are mistaken when we compare war with normal life. Life has never been ‘normal.’ Life is full of crisis, alarms, difficulties, emergencies.”

Lewis suggests that to seek knowledge is the best remedy for confusion and frustration:

“Never, in peace or war, commit your happiness to the future. Happy work is done by the (man) who takes (his) long-term plans somewhat lightly, and works from moment to moment.”

Pursue the life of the mind, he suggested. And focus on the small victories.

I hope you find joy this day in those small things that help you enjoy this big frustrating but beautiful world!